- Home

- Yannick Grannec

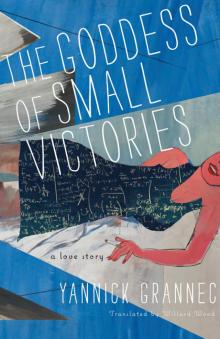

The Goddess of Small Victories Page 4

The Goddess of Small Victories Read online

Page 4

In the winter of 1929, Frau Gödel was still happily unaware of my existence. Her husband having died, she had just moved to Vienna to be near her two sons. Kurt had to jump through hoops to find time for both his suspicious mother and his demanding mistress, while still keeping up with his course work at the university. Although a man who didn’t like to eat, he would have dinner at my house, then join his family for a late second dinner after the theater. He spent part of the night in our bed, ran off to his office at dawn, and then would suffer through long digestive walks in the Prater on his mother’s arm. How did he manage to survive? A rock would have cracked under the pressure. Yet he said himself that he had never worked as well. I didn’t understand that he was using himself up.

After wolfing down his “220,” Kurt jumped out of bed. He brushed his suit, polished his shoes, and checked every button on his clothing. The first time, before he’d explained to me the logic of his dressing-room choreography, I’d laughed. “Shirt buttons, always from the bottom up to avoid misalignment.” He put his left leg into his trousers first because he balanced better on his right and found it lessened the time he was unstable. It was the same for every moment of his life.

He slipped on his mussed shirt without grumbling. So it was true, he was going off to work. He would never appear in his mother’s drawing room looking slovenly. He had accounts with the best tailors in Vienna, he was that elegant. Marianne had little taste for the bohemian chic some students affected. She thought of her sons as display mannequins to advertise the Gödels’ success. After all, textiles were in the family history. Her husband had risen from being foreman in a clothing factory to directing its operations. I tended to be a bit approximate. Despite all my pains, something in my outfit always fell short: a laddered stocking, an ill-fashioned cuff, an off-color pair of gloves. But my fresh-out-of-bed look was exciting enough to Kurt that he spared me his mania. For Kurt, everything assumed extreme proportions, but he applied his sartorial terrorism only to himself. What I had first thought was snobbishness or a bourgeois holdover was a necessity of survival. Kurt wore his suits to face the world. Without them, he had no body. He put back on the paraphernalia of a human being every morning, and it had to be impeccable since it advertised his normality. I later understood that he had so little faith in his mental balance that he laid a grid of ordinariness over his life: a normal outfit, a normal house, a normal life. And I was an ordinary woman.

7

“But it isn’t my birthday.” Adele hesitated to take off her cap. She didn’t want to expose her thinly thatched skull. Anna knelt down, pretending to search her bag for a mirror that she had already found. When she rose to her feet, Mrs. Gödel was wearing her present: a soft blue-gray turban.

“You’re beautiful, Adele! You look like Simone de Beauvoir. It goes with your eyes.”

The old lady looked at herself indulgently.

“You called me by my first name. I don’t have a problem with that. But please stop resorting to it according to circumstances. I’m not senile.”

She smoothed the tissue paper and folded it into a perfect square.

“Gladys is bound to tell me that it makes me look old.”

“Since when have you listened to the opinions of others?”

“You think she’s harmless, but she’s a nuisance. She paws through my belongings.”

“I think I’ve gotten the message.”

“Gladys is secretly venomous. Seeing too much of her can kill you in the long run. She went through three husbands.”

“She’s still on the prowl.”

“Some women never have enough.”

She wiped the mirror with her sleeve before giving it back to Anna.

“So, what is the price tag on your generosity? I wasn’t born yesterday, young lady. Presents are always attached to a cost.”

“It has nothing to do with the Nachlass. I’d like to ask you a personal question, if I may. I’ve been wondering … what you talked about with your husband.”

“You’re always so apologetic. It’s exhausting.”

Adele stored the folded paper in her bedside stand. Anna, not knowing what to do with her hands, tucked them between her thighs.

“What do your parents do?”

“They are both history professors.”

“Rivals?”

“Colleagues.”

“So your parents were intellectuals, but when they went for a walk on Sunday, I’m sure they held hands.”

“They talked to each other a lot.”

She listened calmly to her lie. Had she been honest, Anna would have replaced “talked to” with “shouted at.” They competed over everything, even their child. The lectures of one answered an argument by the other, when they weren’t fighting outright. They waited for their daughter to enter the university before signing a tacit truce. Each had staked out a separate territory, large enough to provide a field for her greatness and his. She, Rachel, went to Berkeley and the West Coast, while George, closer to home, scaled Harvard’s walls. Anna stayed on in Princeton, alone in a town she had always wanted to leave.

“How did they meet?”

“They were students.”

“Does it shock you that a woman like me ended up with a great mind like him?”

“I see great minds all around me, and I’m not impressed by them. But your husband is a legend, even among the great and the good. He was known to be unusually hermetic.”

“We were a couple. Don’t go digging beyond that.”

“And you talked about his work at the dinner table? Today I proved the possibility of space-time travel, would you pass the salt, darling?”

“Was that how it was at your house?”

“I didn’t have meals with my parents.”

“I see. A middle-class upbringing?”

“Prophylaxy.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I had an old-fashioned upbringing.”

Anna’s childhood was continually beset with domestic chaos, carefully kept behind padded doors. Dinners alone with the governess, private schools, dance and music lessons, smocked dresses, and a general inspection before being trotted out into company. Returning from parties where her mother had flitted around the room and her father had pontificated in a corner, she would curl up in the backseat of the car pretending to be asleep to avoid being asphyxiated by their conversation.

The young woman smiled bitterly, and Adele chose to examine her fingers.

Apparently satisfied, Adele said, “To be perfectly frank, at the start of our relation, I harassed him. I couldn’t stand to be left out. I had no access to the greater part of his life. But I had to learn my place. It wasn’t why I was there. It really was beyond me, even if I didn’t want to admit it! And … we had other worries.”

Anna poured the old woman a glass of water for her dry mouth. Adele took it with a hesitant hand. She tried unsuccessfully to keep it from trembling.

“Kurt was searching for perfection and opposed to any idea of vulgarization. It implies a kind of compromise and inexactitude. What I know about his work I gleaned from others. I listened a great deal.”

“When did you realize how important he was?”

“Right away. He was a small star at the university.”

“Were you present at the birth of the incompleteness theorem?”

“Why? Are you planning to write a book?”

“I’d like to hear your version. The theorem became a kind of legend to a group of initiates.”

“It always made me laugh, all these people talking about that fucking theorem. The truth is, I would be surprised if even half of them understood it. And then there are the people who use it to demonstrate anything and everything! I know the limits to my understanding. And they are not due to laziness.”

“Don’t your limits make you angry?”

“Why fight something you can’t do anything about?”

“It doesn’t sound like you.”

“You think you know me already?”

“There’s more to you than you let on. But why me? Why do you let me come back and visit?”

“You didn’t hesitate to strike back at me. I hate condescension. And I like your mix of apologeticness and insolence. I’d like to find out what you’re hiding under that first-communion skirt of yours.”

Deftly, she tucked a stray lock of hair under her turban.

“Do you know what Albert used to say? Yes, Einstein was one of our friends. A conversation stopper, isn’t it? Ach! How he bored us with saying it!”

Anna leaned in so as not to miss a word.

“ ‘The most beautiful and deepest experience a man can have is the sense of the mysterious.’ Of course, it can be understood as relating to faith. I read it differently. I’ve brushed up against mystery. Telling you the facts will never transmit the experience.”

“Tell it to me as a good story. I won’t write a report when I get back to the office. It has nothing to do with them. Just you and me, and a cup of tea.”

“I’d prefer a little bourbon.”

“It’s still daylight out.”

“Then a sip of sherry.”

8

AUGUST 1930

The Incompleteness Café

I have refrained from making truth an idol, preferring to leave it to its more modest name of exactitude.

—Marguerite Yourcenar, The Abyss

On my nights off, I waited for him outside the Café Reichsrat across from the university. It wasn’t my sort of café, being more for talking than drinking. The talk was always of rebuilding the world, a project I saw no need for. On that night the meeting was to focus on preparations for a study trip to Königsberg. I was perfectly happy not to be going, as a conference on the “epistemology of the exact sciences” was no sort of tryst. The days before the meeting, Kurt hummed with a particular, keen vibration. He was enthusiastic, a new state for him. He was in a hurry to present his work.

I was cooling my heels under the arcades when he finally emerged from the café, long after most of the others had left. I was thirsty, hungry, and planning to make a scene, just on principle. From the way his shoulders were hunched, I knew it was the wrong moment.

“Do you want to go out to dinner?”

“We don’t have to.”

He buttoned his jacket carefully. It no longer had the impeccable drape of the previous summer. It seemed to belong to another, stouter man.

“Let’s walk for a bit, if you don’t mind.”

For him “walking” meant cloaking himself in silence. After a few minutes, I couldn’t bear it any longer. What can you do except talk, to solace a man who refuses to eat or to touch you? I knew of no better remedy for anxiety.

“Why do you persist in meeting with this Circle when you don’t share their ideas?”

“They help me think, and I need to get my research in circulation. I have to publish my thesis to qualify for teaching.”

“You look like a little boy who’s been disappointed by his Christmas presents.”

He turned up his coat collar and stuck his hands in his pockets, unbothered by the damp night air. I linked my arm in his.

“I dropped a bomb on the table, and everyone patted me on the back, called for the check, and … that was it.”

I shivered too. From hunger, probably.

“You’re sure of yourself? You haven’t made any errors in calculation?”

He dropped my arm and chose another column of paving stones along which to advance.

“Adele, my proof is irreproachable.”

“I’m sure that’s true. I know the way you open a window three times to make sure it’s closed.”

A group of revelers hurtled into us. I galloped in my high heels to catch up with Kurt. He hadn’t paused in his train of thought, and I had to strain to follow it.

“Charles Darwin said that a mathematician is a blind man in a dark room looking for a black cat that isn’t there. I, on the other hand, stand in the purest light.”

“How can they not believe you, then? Your field is certainty. Everyone knows that two plus two equal four. This is a truth that will always stand!”

“Some truths are temporary conventions. Two and two don’t always equal four.”

“But come on, if I count it out on my fingers …”

“We stopped basing mathematics on felt experience a long time ago. In fact, we make a point of manipulating nonsubjective objects.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I hold you in great respect, Adele, but some subjects are truly beyond you. We’ve talked about this before.”

“Sometimes, you can move a complex idea forward by trying to state it simply.”

“Some ideas can’t be stated simply in ordinary language.”

“That’s exactly it! You imagine yourselves to be gods! You’d do better to take an occasional interest in what’s going on around you! Are you aware of people’s suffering? Do you have the slightest concern about the coming elections? I read the newspaper, Kurt, it’s written in the language of men!”

“You should learn to control your temper, Adele.”

He took my hand, the first time he had ever done so in public, and we walked under the silent arcades to the cross street.

“In certain cases, one can prove a thing and its opposite.”

“That’s nothing new, I specialize in it.”

“In mathematics, this is known as ‘inconsistency.’ In you, Adele, it’s contrariness. I have just proved that there exist mathematical truths that cannot be demonstrated. That is incompleteness.”

“And that’s all?”

Irony never served as a bridge between us; he saw it as a simple error in communication. Sometimes it forced him to reformulate, find an acceptable image. These rare efforts were real proofs of love: a temporary relaxation of the tyranny of perfection.

“Imagine a being with eternal life, a being that spent its immortality taking stock of mathematical truths. Defining what’s true and what’s false. It could never come to the end of its task.”

“God, in short.”

He hesitated a moment before walking forward, the wear of the pavement obscuring the path he’d set for himself.

“Mathematicians are like children who pile truth bricks one on top of another, building a wall to fill the emptiness of space. They ask if all the bricks are solid, if some might not make the whole edifice crumble. I proved that in one part of the wall, certain bricks are inaccessible. As a result, we’ll never be able to verify that the entire wall is solid.”

“You horrible brat, it isn’t nice to spoil other people’s games!”

“My game too, possibly, but at the outset I never thought I would destroy it—just the opposite.3

“Why don’t you go back to physics, then?”

“Everything in physics is even more uncertain. Especially now. It would take too long to explain it all. Physicists are part of the confusion. They’re looking for a bucket big enough to cover the buckets of the ones who came before. Theories that are even more global.”

“Each of them is trying to piss farther than his playmates.”

“I’m sure my colleagues will fully appreciate your views on scientists, Adele.”

“Bring them on! I’ll teach them about life.”

For several seconds, he considered unleashing me in the cloistered halls of the university by way of retaliation. But the thought didn’t help to relax him.

“They don’t respect me. I know what they’re saying behind my back. Even Wittgenstein, although he distrusts the positivists, takes me for a conjurer, a manipulator of symbols.”4

“That man hasn’t got all his marbles. He gave his fortune away to some poets and went off to live in a cabin. You’d put your trust in him?”

“Adele!”

“I’m trying to make you laugh, Kurt, but I’m starting to realize that we’re facing an on-to-log-i-cal impossibility.”

“You learned that word in the Nachtfalter’s coat room?”

We reached his street. From a distance I could see a light on in the windows of his apartment: his mother never went to sleep until she heard his footsteps in the hallway. To stay out all night was to sentence her to wakefulness. We joked about it. Sometimes. That night, the lonely one was to be me.

“In a nutshell, you used this logic of yours to prove that there are limits to logic?”

“No, I demonstrated the limits of formalism. The limits of mathematics as we know it.”

“So you didn’t tip all of their precious mathematics into the garbage! You just proved to them that they would never be gods.”

“Leave God out of all this. It’s their faith in the all-powerfulness of mathematical thinking that has been breached. I’ve killed Euclid, struck down Hilbert … I’ve committed sacrilege.”

He got out his travel kit, a sign by which he often brought debates to a close: Don’t come too close, my mother might see you from the window.

“I need to work on my speech. I am meeting Carnap in two days.”

“That bullfrog, he’d like to think he’s bigger than—”

“Adele! Carnap is a good man, he’s helped me enormously.”

“He’s a Red. And he’s going to be in trouble soon enough.”

“You don’t know the first thing about politics.”

“I keep my ear to the ground. And what I’m hearing isn’t so favorable to the intelligentsia, believe me!”

“Adele, I have enough to worry about already. I’m very tired.”

The Goddess of Small Victories

The Goddess of Small Victories