- Home

- Yannick Grannec

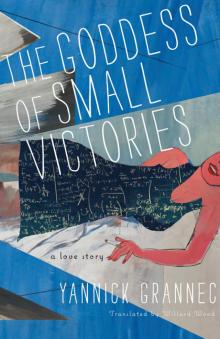

The Goddess of Small Victories

The Goddess of Small Victories Read online

Kurt Gödel, Institute for Advanced Study, 1956

(photo by Arnold Newman/Getty Images)

Copyright © S. N. Éditions Anne Carrière, Paris, 2012

Originally published in French as La Déesse des petites victoires by S. N.

Éditions Anne Carrière, Paris, France, in 2012.

Translation copyright © 2014 Willard Wood

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas

Text Designer: Julie Fry

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Grannec, Yannick.

[La déesse des petites victoires. English]

The goddess of small victories / by Yannick Grannec; translated from the French by Willard Wood.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59051-636-2 (hardcover) — ISBN 978-1-59051-637-9 (ebook)

1. Gödel, Kurt—Fiction. 2. Mathematicians—Fiction. 3. World War, 1939-1945—Refugees—Austria—Fiction. I. Wood, Willard, translator. II. Title.

PQ2707.R37D4413 2014

843’.92—dc23

2013049320

Publisher’s Note:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Chapter 1 - October 1980: Pine Run Retirement Home Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Chapter 2 - 1928: Back When I Was Beautiful

Chapter 3

Chapter 4 - 1928: The Circle

Chapter 5

Chapter 6 - 1929: The Windows Open, Even in Winter

Chapter 7

Chapter 8 - August 1930: The Incompleteness Café

Chapter 9

Chapter 10 - 1931: The Flaw

Chapter 11

Chapter 12 - 1933: Separation

Chapter 13

Chapter 14 - January 1936: Necessary but Not Sufficient

Chapter 15

Chapter 16 - 1936: The Worst Year of My Life6

Chapter 17

Chapter 18 - 1937: The Pact

Chapter 19

Chapter 20 - 1938: The Year of Decision

Chapter 21

Chapter 22 - 1939: Adele’s Umbrella

Chapter 23

Chapter 24 - 1940: Flight

Chapter 25

Chapter 26 - Summer 1942: Blue Hill Inn

Chapter 27

Chapter 28 - 1944: An Atomic Soufflé

Chapter 29

Chapter 30 - 1946: Ambulatory Digressions Going

Chapter 31

Chapter 32 - 1946: Ambulatory Digressions Coming Back

Chapter 33

Chapter 34 - December 5, 1947: So Help Me God!

Chapter 35

Chapter 36 - 1949: The Goddess of Small Victories

Chapter 37

Chapter 38 - 1950: Witch

Chapter 39

Chapter 40 - 1952: A Couch for Three

Chapter 41

Chapter 42 - 1954: Alice in Atomicland

Chapter 43

Chapter 44 - April 13, 1955: The One-Eyed Man, the Blind Man, and the Third Eye

Chapter 45

Chapter 46 - 1958: Papa Albert’s Dead and Gone

Chapter 47

Chapter 48 - November 22, 1963: Boredom Is a Surer Poison

Chapter 49

Chapter 50 - 1970: Almost Dead

Chapter 51

Chapter 52 - 1973-1978: So Old a Love

Chapter 53

Chapter 54 - 1978: Alone

Chapter 55

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Notes

Further Reading: Select Bibliography

Credits

A Conversation with Yannick Grannec

There are two ways of spreading light: to be the candle or the mirror that reflects it.

—Edith Wharton

1

OCTOBER 1980

PINE RUN RETIREMENT HOME

DOYLESTOWN, PENNSYLVANIA

Anna waited at the exact boundary between the hallway and the bedroom while the nurse pleaded her case. The young woman concentrated on every sound, trying to contain her anxiety: wisps of conversation, raised voices, televisions droning, the swish of doors being opened, the clatter of metal carts.

Her back ached but still she kept her bag shouldered. She moved a step forward to be in the center of the linoleum square marking the room’s threshold. She fingered the index card in her pocket to give herself courage. Her well-reasoned argument was written out in block capitals.

The nurse patted the old woman’s age-speckled hand, straightened her cap, and adjusted her pillows.

“Now Mrs. Gödel, you don’t have so many visitors that you can go turning people away. Let her in. Have a little sport with her. It will give you some exercise!”

On her way out, the nurse gave Anna a small smile of commiseration. You have to know how to handle her. Good luck, sweetheart. That was all the help she could give. The young woman hesitated. Not that she hadn’t prepared for this interview: she would lay out the salient points of her case, articulating each word carefully and with enthusiasm. But under the steady, unwelcoming gaze of the room’s bedridden occupant, she changed her mind. Better to be neutral, to disappear behind the unobtrusive outfit she had selected that morning, a beige plaid skirt and matching twinset. She was certain that Mrs. Gödel was not one of those old ladies you call by their first names because they’re going to die soon. Anna’s index card would stay in her pocket.

“I’m honored to meet you, Mrs. Gödel. My name is Anna Roth.”

“Roth? Are you Jewish?”

Anna smiled at the thick Viennese accent, refusing to be intimidated.

“Is that important to you?”

“Not in the slightest. I like to know where people come from. I travel vicariously, now that …”

She tried to straighten up in bed and a painful grimace crossed her face. Impulsively, Anna reached out to help. An icy glare from Mrs. Gödel stopped her.

“So, you work for the Institute for Advanced Study? You’re terribly young to be moldering away in that retirement home for scientists. But enough. We both know what brings you here.”

“We’re in a position to make you an offer.”

“What total imbeciles! Money is not the issue!”

Anna felt a wave of panic. Whatever you do, don’t respond. She hardly dared draw breath, despite her mounting nausea from the smell of disinfectant and bad coffee. She had never liked old people and hospitals. The old lady poked under her cap and twirled a lock of hair but didn’t meet her eyes. “Go away, young lady. You don’t belong here.”

Back in the lobby, Anna collapsed onto a brown leatherette chair. She reached for the box of liqueur-filled chocolates on the nearby side table. She had left it there when she arrived, suddenly realizing that sweets might be a bad idea if Mrs. Gödel could no longer eat them. But now the box was empty. Anna bit down instead on her thumbnail. She had tried and failed. The Institute would have to wait until Gödel’s widow died and just pray to all the

Rhine gods that she not destroy anything precious in the meantime. The young woman would so have liked to be the first to inventory Kurt Gödel’s papers, his Nachlass. She looked back with mortification at her feeble preparations. In the end, she’d been cast aside with a flick of the hand.

She carefully tore up her index card and distributed the pieces in the compartments of the chocolate box. She’d been warned about the Gödel widow’s stubborn vulgarity. No one had ever managed to reason with her, neither her friends nor even the director of the Institute. How could this madwoman cling as she did to this trove of cultural patrimony, which belonged, by right, to all mankind? Who did she think she was? Anna stood up. I couldn’t screw this up more if I tried, I’m going back.

She gave a perfunctory knock and went in. Mrs. Gödel seemed unsurprised at the intrusion.

“You’re not mercenary, and you’re not crazy,” said Anna. “All you really want is to provoke them! The power to hinder is all you have left.”

“And what about them? What are they cooking up this time? Throwing some kind of secretary at me? A nice girl but not too pretty so that my old lady’s sensibilities won’t be ruffled?”

“You realize perfectly the value of these archives to posterity.”

“Do you know? Posterity can go straight to hell! And those archives of yours, I just might burn them. I particularly want to use some of the letters from my mother-in-law for toilet paper.”

“You don’t have the right to destroy those documents!”

“And what do they think at the Institute? That the fat Austrian lady is unable to judge the importance of those papers? I lived with the man for more than fifty years. I know goddamn well how great a man he is! I carried his train and polished his crown all my life! You are just another of the prim, tight-sphinctered Princeton types wondering why a genius would marry a cow like me. Ask posterity for an answer! No one has ever wondered what I might have seen in him!”

“You’re angry, but your anger is not really directed at the Institute.”

The widow Gödel looked at Anna, her faded blue pupils and bloodshot eyes matching the pattern of her flowered nightgown.

“He’s dead, Mrs. Gödel. No one can help that.”

The old woman twisted her wedding band around her yellowed finger.

“Out of what drawer of doctoral candidates did they pluck you?”

“I have no particular degree in science. I’m an archivist at the IAS.”

“Kurt took all his notes in Gabelsberger, a shorthand used in Germany but now forgotten. If I gave you his papers, you wouldn’t know what to do with them!”

“I know Gabelsberger.”

The old woman’s hands stopped playing with her ring and gripped the collar of her bathrobe.

“How is that possible? There are maybe three people in the world …”

“Meine Grossmutter war Deutsche. Sie hat mir die Schrift beigebracht.” My grandmother was German. She taught me how to write it.

“They always think they are so clever! I am going to trust you because you can spout a few words in German? For your information, Miss Librarian, I am Viennese, not German. And the three people who can read Gabelsberger don’t intersect with the ten people who can understand Kurt Gödel. Which neither you nor I are capable of doing.”

“I don’t claim to understand him. I’d like to make myself useful by inventorying the contents of the Nachlass so that others, who truly are qualified, can study it. This is not some airy fantasy, and it’s not a heist. It’s a mark of respect, Madam.”

“Why are you all hunched over? It makes you look old. Sit up straight!”

The young woman corrected her posture. All her life she had been hearing, “Anna, don’t slouch!”

“Those chocolates, where did they come from?”

“Oh, how did you guess?”

“A question of logic. Number one, you are a sensible girl, well brought up, you wouldn’t arrive here empty-handed. Number two …”

She gestured toward the door with her chin. Anna turned and saw a tiny wrinkled creature standing quietly in the doorway. Her pink, spangled angora sweater was smeared with chocolate.

“It’s teatime, Adele.”

“I’m coming, Gladys. Since you want to be useful, young lady, start by helping me out of this chromed coffin.”

Anna brought the wheelchair next to the bed, lowered the metal rails, and drew back the sheets. She hesitated to touch the old lady. Pivoting her body, Gödel’s widow set her trembling feet on the floor, then with a smile invited the young woman to help her up. Anna grabbed her under the arms. Once she was seated in the wheelchair, Adele gave a sigh of comfort, and Anna a sigh of relief, surprised at having so easily rediscovered movements she had thought erased from her memory. Her grandmother Josepha trailed the same scent of lavender in her wake. Anna shook off her nostalgia. A lump in her throat was a small price to pay for such a promising first contact.

“Would you really like to give me pleasure, Miss Roth? Then next time bring a bottle of bourbon with you. The only thing we manage to smuggle into this place is sherry. I despise sherry. Besides, I’ve always hated the British.”

“Then I can come back?”

“Mag sein …” Maybe so.

2

1928

Back When I Was Beautiful

To fall in love is to create a religion that has a fallible god.

—Jorge Luis Borges, Other Inquisitions

I noticed him long before he ever looked at me. We lived on the same street in Vienna, in the Josefstadt district next to the university—he with his brother, Rudolf, and I with my parents. It was in the early hours of the morning, I was walking back to my house—alone as usual—from the Nachtfalter, “the Moth,” the cabaret where I worked. I’d never been so naïve as to believe in the disinterest of customers who offered to accompany me home after my shift. My legs knew the route by heart, but I couldn’t afford to lower my guard. The city was murky. Horrible rumors circulated about gangs that snatched young women off the street and sold them to the brothels of Berlin-Babylon. So here I was, Adele Porkert, no longer a girl exactly but looking about twenty, slinking along the walls and starting at shadows. “Porkert,” I told myself, “you’ll be out of these damn shoes within five minutes and tucked up in bed within ten.” When I’d almost reached my door, I noticed a figure on the opposite sidewalk, a smallish man wrapped in a heavy coat, wearing a dark fedora and a scarf across his face. His hands were clasped behind his back and he walked slowly, as though taking an after-dinner stroll. I picked up my pace. My stomach knotted into a ball. My gut rarely misled me. No one goes for a walk at five o’clock in the morning. If you’re out at dawn and you’re on the right side of the human comedy, then you’re returning home from a nightclub or you’re on your way to work. Besides, no one would have bundled up like that on such a mild night. I tightened my buttocks and ran the last few yards, gauging my chances of rousing the neighbors by screaming. I had my keys in one hand and a little bag of ground pepper in the other. My friend Lieesa had showed me how I could use these to blind an attacker and lacerate his face. No sooner did I reach my building than I darted inside and slammed the thin wooden door shut behind me. What a scare he’d given me! I watched him from behind the curtain of my bedroom window: he continued to stroll. When I encountered my ghost the next day at the same time, I didn’t hasten my pace. For two weeks I ran into him every morning. Not once did he seem aware of my presence. Apparently he didn’t see anything. I began walking on his side of the street and took care to brush against him when passing. He never even raised his head. The girls at the club had a good laugh at my story of almost using the pepper. Then one day he wasn’t there. I left work a little earlier, a little later, just in case. But he had vanished.

Until one night in the cloakroom at the Nachtfalter when he handed me his heavy coat, a coat much too warm for that time of year. Its owner was a handsome dark-haired man in his early twenties with blue eyes blurred be

hind the severe black circles of his glasses. I couldn’t help taunting him.

“Good evening, Herr Ghost from the Lange Gasse.”

He looked at me as though I were the Commendatore himself, then turned to the two friends who accompanied him. One of them I recognized as Marcel Natkin, a regular at my father’s store. They sniggered as young men do when they are a little embarrassed, even the best educated. He wasn’t the type to go putting the make on hatcheck girls.

As he didn’t answer and I was busy with a sudden flood of customers, I decided not to press the point. I took the young men’s overcoats and ducked between the coat hangers.

Toward one o’clock, I put on my stage costume, a modest enough affair given how much some girls exposed of themselves at the fashionable clubs. It was a saucy sailor’s outfit: a short-sleeved shirt, white satin shorts, and a flowing navy-blue necktie. And I was of course fully made up. Amazing how much paint I wore in those days! I did my number with the other girls—Lieesa flubbed her dance routine again—then we turned the stage over to the comic singer. I saw the three young men sitting near the stage, all of them getting an eyeful of our exposed legs, my ghost not least among them. I resumed my station at the hatcheck stand. The Nachtfalter was a small club. We all had to do a little of everything—dancing and selling cigarettes between appearances onstage.

When the young man joined me a short while later, it was my friends’ turn to snigger.

“Excuse me, Fräulein, do we know each other?”

“I often pass you on the Lange Gasse.”

I hunted around under the counter to give myself something to do. He waited impassively.

“I live at number 65,” I said, “and you at number 72. But during the day I dress differently.”

I felt an urge to tease him. His muteness was endearing. He seemed harmless.

“What are you doing every night outdoors, other than watching your shoes move?”

“I like to think as I walk, that is … I think better when I’m walking.”

“And what is so terribly fascinating to think about?”

The Goddess of Small Victories

The Goddess of Small Victories